Breaking the Cycle

Support and compassion for women amid addiction

As Angela Wilson walks through the city center in Glasgow, she recounts living on the streets with an addiction — the extremes she took to get drugs, the work she did to pay for more.

“People don’t choose to wake up in the morning and become an addict,” Wilson said. In Scotland “there’s always a circumstance … a situation, a story behind it."

Despite a growing range of resources in Glasgow’s city center where the drug crisis is highest, women continue to be the most vulnerable population on the streets, and there’s a strong need for more women specific facilities, support groups and child support for mothers.

According to the latest data, the number of women dying from drug-related deaths in Scotland between January and March 2023 jumped 14%.

Wilson witnessed it firsthand in her role as a community support worker with Simon Community Scotland, assisting those on the street experiencing homelessness and addiction daily.

During her morning shift through the city, Wilson calmly walks through alleyways and side streets on a mission to provide as much care as possible to people on her route. She's a familiar face to those she approaches, and many greet her first.

The vibe is one of trust.

“Unless you’ve been out here in the streets, unless you’ve experienced addiction, you will never understand,” Wilson said.

Meet Glasgow community support worker Angela Wilson

Wilson works in the city center of Glasgow. As a member of the street team, she provides resources to those in need while cultivating personal relationships.

Video by Anjelica Rubin

In Scotland, women who use drugs are not only more likely to carry the trauma of domestic abuse, sex work and greater stigma than their male counterparts, they are also more likely to be caring for children and have them taken away, according to recent research from With You, one of the largest providers of treatment and support services in the U.K.

Recovery Café

Women gather in the Calton Heritage and Learning Centre to share their journey with addiction. The women-run cafés offer support and community.

Video by Anjelica Rubin

Which is why North East Recovery Community in Glasgow is trying to change the narrative — one recovery café at a time.

Run by volunteers at different stages in their own recovery, the cafés offer support, resources and an outlet for women to connect with each other through conversation and shared lived experiences.

Formed in 2014, NERC is the umbrella organization for six recovery cafés in the city, including Recovery Empowers North East Women or RENEW.

Sarah Jane McMehon is a development worker for NERC and oversees the RENEW program. She discovered recovery cafés while in treatment herself.

“When I got clean and sober, when I was in rehab, I didn’t like women,” McMehon said. “I always thought women were after something from me. I couldn’t manipulate them (like) I could manipulate men.”

McMehon said once she realized the women around her only wanted to support her recovery, she began gaining confidence as a participant and then as a volunteer. After opening another one café under the NERC umbrella, she set her sights on opening another because more women needed a safe space.

Since McMehon’s place opened 10 years ago it has become one of the most popular cafés within NERC. Every Friday, it is filled with women of all ages. Centered around a circle discussion model, it runs on the premise that each of its participants will be open and transparent with each other.

It is funded by the Scottish Government’s Alcohol and Drug Partnerships, a multi-agency effort focused on alcohol and drug misuse issues in local areas. ADP money is filtered down to local municipalities, with allotments then awarded based on size and area that the funds will cover.

McMehon said additional funding will come from raffles, fundraisers and community support for the café, which recently became a charity.

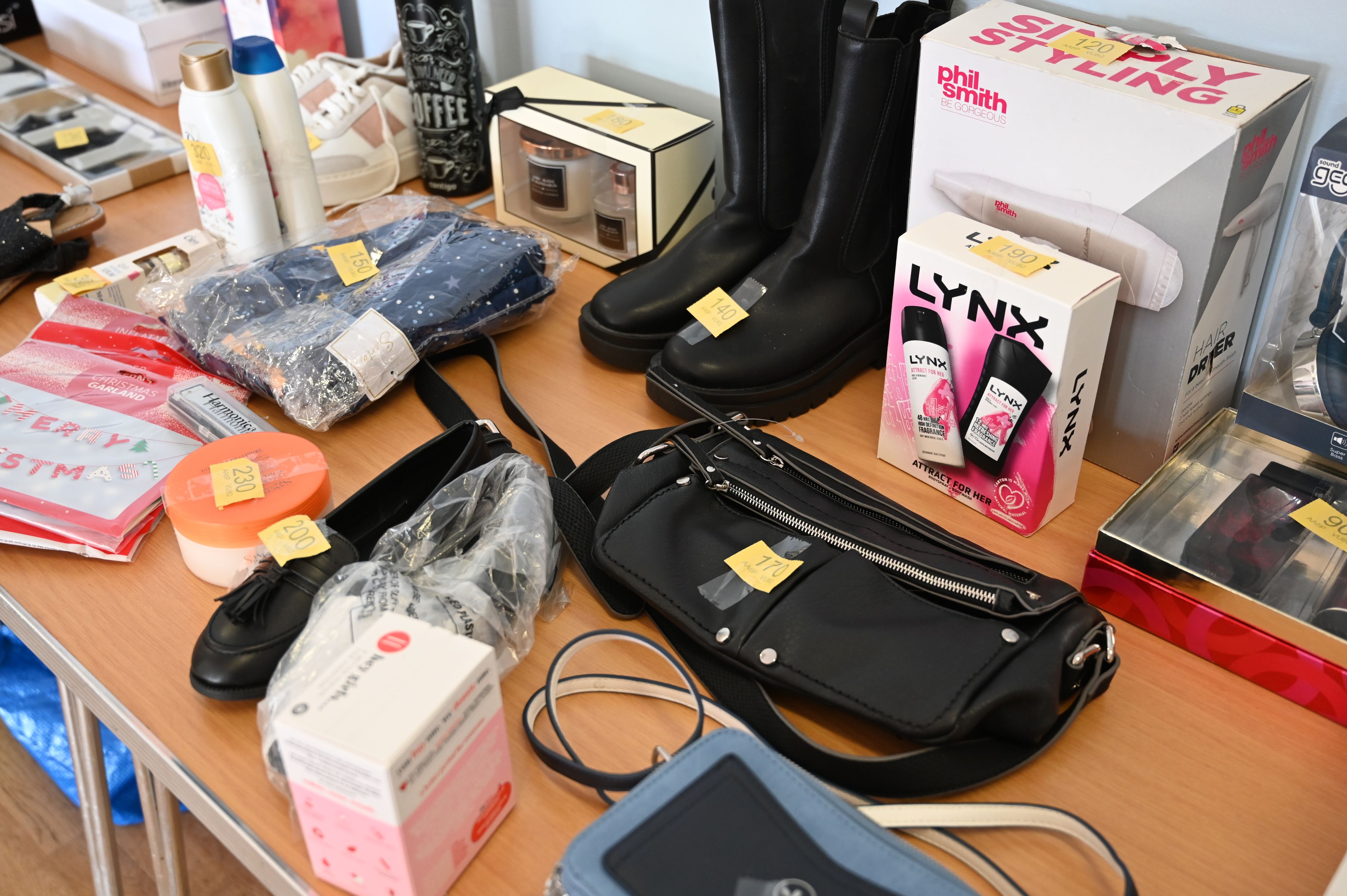

Pamphlets are placed strategically around the room. A social worker has a table in the back corner for women struggling amid Glasgow’s housing crisis — Scottish Government figures show homelessness has returned to pre-pandemic levels — and game prizes consist of practical items like cleaning supplies or menstruation products.

Sharon Caven is a volunteer at RENEW and first became involved seven years ago after meeting volunteers who encouraged her to attend the café.

She started using drugs when she was 11 or 12 years old, starting with alcohol and cannabis. Then came the ecstasy and street valium.

At 15, she started using heroin. Her sister’s boyfriend sold it to her.

“I wasn’t aware of what I was taking,” Caven said. “(But) everyone else was taking it.”

In many cases, an addiction is not identified early enough, the key needed to break the cycle, according to Caven, who said she became concerned about her reliance on heroin early and sought out her own help.

But because Caven was “only” smoking heroin, her general practitioner told her she “wasn’t putting herself at risk” and refused to give her any help.

“I was 17 when I started prostituting,” Caven said. “Then as my addiction grew, I started injecting. (I couldn’t work anymore so) I ended up on the street.”

Driven into sex work to get money for drugs, Caven was a victim of rape, beatings and assaults. She was 19 when she became pregnant and placed on a methadone prescription.

Caven stabilized, managing to stay clean for over a year and had her baby. But after being awarded 11,000 pounds of compensation money due to the outcome of a court trial, she “blew it all” on drugs within four months.

For the next six to seven years, Caven was back on the streets.

“Addiction is an illness. It’s not a choice,” Caven said. “People are brought up in poverty in the Glasgow area and it’s a lot of learned behaviors from adults and peers, guardians and parents who are supposed to be showing a good way of living.”

Scottish government poverty statistics showed that, between 2019-22, 36% of single women with children were living in poverty and between 2019-21, the life expectancy for women in the most deprived areas of Scotland was 25 years lower than in the least deprived areas, according to the National Records of Scotland.

When her child’s father died, Caven fed off a new motivation not to leave her child an orphan. Now she credits women-centered recovery groups like RENEW with helping her begin again. She hasn’t used illicit drugs in 15 years.

“There’s still a lot of stigma towards you being treated equally if you have an addiction in your past,” Caven said.

A community member speaks at the beginning of a recovery café meeting. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

A community member speaks at the beginning of a recovery café meeting. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Sharon Caven and other North East Recovery Community volunteers lead a discussion circle at the weekly café in Glasgow. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Sharon Caven and other North East Recovery Community volunteers lead a discussion circle at the weekly café in Glasgow. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Caven at North East Recovery Community's recovery café in Glasgow. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Caven at North East Recovery Community's recovery café in Glasgow. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Maureen's story

Sarah Jane McMehon, a lead for NERC, shares a story of Maureen Holmes who was a part of the recovery café gatherings in Glasgow. The women's café group saw her getting on with her recovery. Shortly after she got clean, Maureen was diagnosed with cancer and died. The women raised funds to put up a bench outside of the space where they meet every Friday — to honor Maureen’s life.

Video by Anjelica Rubin

McMehon said stigma as well as the rate at which women can relapse is why she makes sure the café functions as a family.

“I’ll look after volunteers, and they’ll look after participants. I’m like their mammy,” McMehon said. “If they don’t turn up, I’m phoning them, if they don’t answer, I’m running to the house. I need to know they're alright.”

Sometimes efforts to ease the drug problem in Glasgow have the unintended effect of highlighting how stigmatization hits women harder than men.

For example, the Enhanced Drug Treatment Service, the country’s first pharmaceutical grade heroin-assisted treatment center in Glasgow which opened in 2019.

Saket Priyadarshi, the associate medical director of Alcohol and Drug Recovery Services in Glasgow, said the ratio of men to women who use the heroin-assisted treatment program is 5:1, meaning just four women use it, compared to 20 men.

Inside North East Recovery Community's recovery cafés:

The café is held at the Calton Heritage and Learning Centre each week. Photo by Olivia Estright

A volunteer laughs during the discussion component of the café. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Women have the opportunity to share where they are at in their recovery process. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

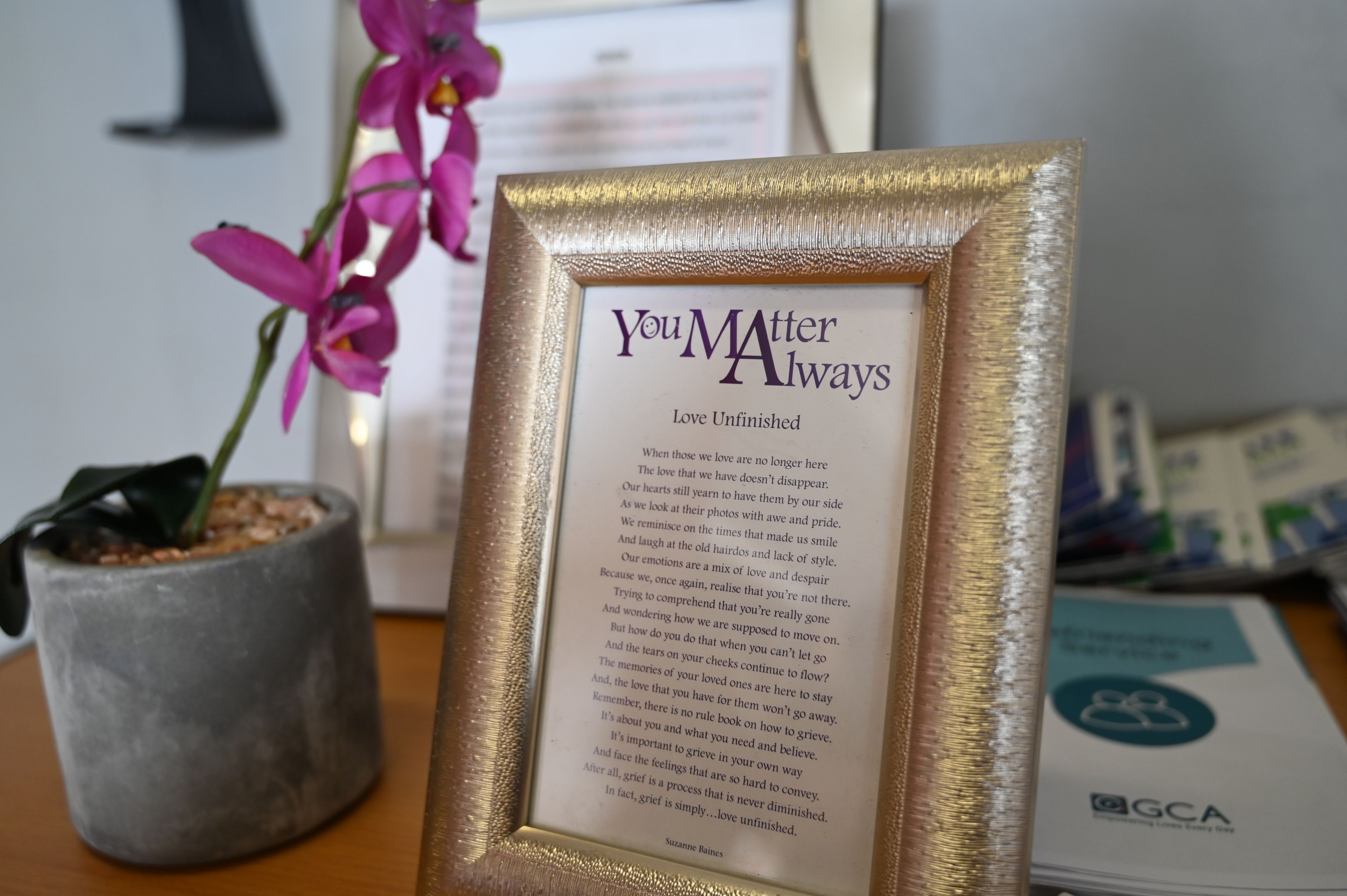

A sign mourning losses sits on a table in the support group's room. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Representatives from different social services attend the support group. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Women play Bingo for the chance to win practical prizes. Photo by Olivia Estright

Sarah Jane McMehon, creator and supervisor of the RENEW café. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

A bench outside dedicated to Maureen, a former participant of the café. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Pamphlets lay on a table as resources for women. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

A volunteer listens to a participant during the discussion period. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Shoes, toiletries and household items are given out during Bingo and raffles. Photo by Mila Sanina

Volunteers listen and show support for each woman who shares her story. Photo by Mila Sanina

A few blocks away, Simon Community Scotland is opening a new women's-only center this year.

The women’s center will be called the Connect Hub and will serve as a safe space for women to access fast support. There will be group work, a kitchen, fresh food, activities for children and a less clinical approach to a doctor’s office.

“A lot of parents in addiction suffer a lot from isolation,” Caven said. “There’s fear (that in Scotland) children (can be) removed by social workers if they come forward and say they're struggling a bit, to say they're using drugs.”

Originally, SCS hubs like this one operated on a zero-tolerance model for drug use. But after 17 fatal overdose deaths across their services in a single year, the organization turned to a high-tolerance model, meaning people with addictions can use drugs if necessary on the property.

In 2021, across the organization’s services, there was only one fatal overdose death.

Olivia Conner, a women’s development worker with SCS, said the Connect Hub will have an immediate impact. They are working with a steering group of six women with lived experiences weekly on the design, services and overall planning of the hub.

“They’ve accessed services before, (so they understand) more than anyone what worked and what didn’t,” Conner said, “if you're not catering it to the people you’re supporting, then what’s the point?”

Claire McGregor is one of the women working closely with the SCS development team to open the Connect Hub.

“I get what it's like (when) your wains (children) have to come meet you outside in the city center, how dangerous it is at nighttime,” McGregor said. “Us women have to be bigger, tougher, more stronger than what we are.”

That’s why McGregor said the Connect Hub gives her hope. It’s also why Wilson continues working in the field.

“We come from all different backgrounds and lived experiences," Wilson said. “The fact that support workers have got so much empathy and compassion (for women), it gives me hope that other people who are also not from lived experience backgrounds” will have that same compassion.

Inside Simon Community Scotland's city-wide hubs:

Inside The Access Hub. Photo by Anjelica Rubin.

Siobhan Page, a service leader at The Access Hub. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

In front of SCS headquarters in Glasgow. Photo by Olivia Estright.

Outside of the set location for the Connect Hub. Photo by Olivia Estright.

The Access Hub has a veterinary office for individuals to bring their pets. Photo by Anjelica Rubin.

The Access Hub aims to create a warm environment. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

All hubs have patient rooms. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Flowers will cover the windows in the Connect Hub. Photo by Olivia Estright

The ceiling of The Access Hub. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

Angela Wilson and others in a meeting. Photo by Anjelica Rubin

A sign in front of SCS headquarters in Glasgow. Photo by Anjelica Rubin